This week’s guest post is by Kevin Simler. Kevin is a philosopher and blogger who believes in (pan)critical rationalism, keeping his identity small, and writing as an aid to thinking. This post was first published on his website, Melting Asphalt — one of my favorite sources for fresh critical perspectives on the mind, society, and everything in between.

![]()

At a sleepover when I was 12, a friend told me that he could control his dreams. It didn’t happen every night, he said, but every so often he’d become aware of being in the middle of a dream. Usually at that point he’d wake up, but sometimes, with a delicate act of will, he could remain in the dream long enough to fly around for a bit — or whatever else 12-year-old boys are wont to do in the privacy of their minds.

Art from Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

I called bullshit. In all my experiences, whenever I became conscious of my dreams I would wake up instantly. To be aware of one’s dreaming struck me as physiologically if not logically impossible. But years later I would come to experience these lucid dreams myself. My friend, it turns out, had been right all along.

Every night we spend an hour or so cavorting around in a rich hallucinated fantasyland — and we think nothing of it.

I think we all have these prejudices. But they are a crippling impediment to understanding human consciousness.

So today’s exercise will be to shatter our prejudices about what constitutes a legitimate conscious experience. Incidentally, it will also expand our notion of what it means to be human.

Menagerie of the mind

Evolution has produced some truly bizarre creatures. Mantis shrimp. Immortal jellyfish. Naked mole rats. If these didn’t actually exist, I’d have trouble believing in them (and I’m still not entirely sure about the narwhal).

Mantis shrimp

The brain, too, is capable of some pretty weird stuff. It’s not just a blank slate holding symbolic impressions of what’s happening out in the world. It’s a multi-purpose organ, designed by the same process that made the mantis shrimp and capable of just as many strange and wonderful things.

So just as we like to catalogue life-forms in order to deepen our appreciation of nature, so too can we catalogue our states of consciousness, to better understand what our brain-organs are capable of. Sometimes these states are called “altered,” but I prefer to think of them simply as rare or exotic.

A brain that’s capable of dreaming should be capable of almost anything.

Then there are spiritual or religious experiences, which are characterized by a suppressed ego and a heightened sense of unity. These don’t happen to everyone, but they’re prevalent enough and well-documented. And whatever you might think of the interpretation of a spiritual experience (e.g. the presence of God), the experience itself is, in neurological terms, very real indeed. This will be a common theme today: that we must never let the interpretation of an experience mislead us into thinking the experience itself is illegitimate.

Then there are the states attending to physical illness — stupor, delirium, lightheadedness, or (in extreme cases) out-of-body experiences.

Moods and emotions also correspond to states of consciousness: sadness, fear, surprise, laughter, joy, lust, anxiety, guilt, anger, shame, pride, boredom, and nostalgia.

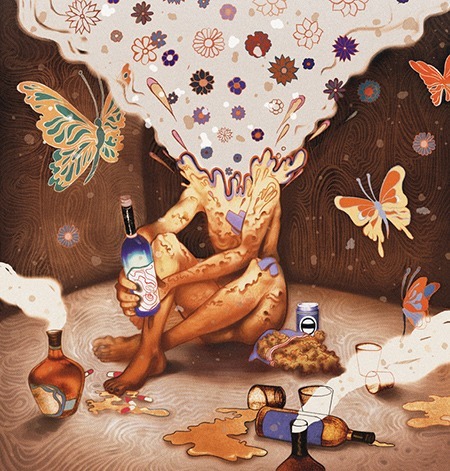

Art by Karla Castaneda

Drugs put us into all kinds of interesting states — being drunk, high, coked-up, focused, mellow, manic, or even egoless. We typically think of these states as somehow unnatural, but they work by tweaking the same neurotransmitters that the brain uses every day. “There is nothing that one can experience on a drug that is not, at some level, an expression of the brain’s potential,” Sam Harris reminds us. “Whatever one has experienced after ingesting a drug… is likely to have been experienced, by someone, somewhere, without it.”

But let’s not forget all the weird things that happen around sleep. Drowsiness, hypnagogia, hypnopompia, the Tetris effect, and of course dreaming itself. Every night we spend an hour or so cavorting around in a rich hallucinated fantasyland — and we think nothing of it. But this should give us pause. A brain that’s capable of dreaming should be capable of almost anything.

And all of this is only the tip of the iceberg — the states that most people have experienced at some point in their lives. In fact the brain is capable of many more and stranger things, especially if we admit into our catalogue all the states attending to brain damage, mental illness, torture, and sleep- or sensory-deprivation. Alien hand syndrome and face-blindness are but two examples.

The question of legitimacy

Mental health is a slippery concept because it depends on social context for meaning. States of consciousness that one society labels as ‘deviant’ or ‘mentally ill’ have been, at other times and places, perfectly acceptable and healthy.

It’s not hard to imagine a world — 500 years from now, say — in which adults have lost the ability to daydream. Children, even infants, will grow up immersed in computer-mediated reality and be bombarded every waking moment with ‘optimal’ stimulation. In such a saturated world, a normal human brain may well become incapable of “day-dreaming” — of pulling up anchor from reality and drifting off into aimless daytime fantasies.

I’m not putting this forward as an actual prediction of what’s likely to happen, but merely as a hypothetical “what-if” scenario.

So what would this future society think of the few remaining people who are prone to “day-dreams”? Theirs will be the brains that, by definition, don’t respond in the normal way to environmental conditioning. It will be easy and tempting, then, to classify such people as mentally ill — to diagnose them with Aimless Imagination Disorder, perhaps. And surely there will be drugs to help keep them attending to reality, i.e., to what’s happening on their screens.

This tendency — to marginalize a conscious experience, label it as deviant, and then deny its historical prevalence — isn’t merely hypothetical. It’s happening right now.

And what will this future society make of us, here in 2013? I suspect they would reject or at least downplay the idea that we were all day-dreamers. Certainly we don’t talk much about our day-dreams, or give them any social weight. In public we rarely acknowledge how often we lose contact with reality to engage in idle fantasies; it comes off as childish, so there’s a very mild taboo around it. Even people who keep diaries write more often about their dreams than their daydreams, at least in terms of explicit references. When we do talk about our daydreams, we focus more on the content than the form, and we don’t call them by their name. We just say, “The other day I was thinking about X.” It may well have been a daydream, but we usually prefer the polite synonym “thinking.”

Art by allison712

And so this phenomenon, which constitutes maybe 10% (?) of our waking consciousness, will leave hardly a trace on the record we leave for future archaeologists. Judged by our artifacts — our books and public speeches, diaries and YouTube videos — we’ll come across as perfectly ‘normal’ to these future archaeologists. They’ll find occasional puzzling references to “daydreaming,” but will be tempted to discount those references in favor of their a priori belief that we weren’t, as an entire society, mentally ill.

This tendency — to marginalize a conscious experience, label it as deviant, and then deny its historical prevalence — isn’t merely hypothetical. It’s happening right now, and has been happening for a millennium or more, here in the West. Both the Church and secular society alike have been marginalizing trance states and hallucinations.

Our goal, today, will be to pick these states up from the gutter, dust them off a bit, give them some clean clothes, and see if we can learn to treat them as legitimate members of society. Just as we’ve learned to accept all races, genders, and sexual identities and orientations, and just as we’re learning to accept autism and ADD, so too might we learn to accept trances and hallucinations as ways-of-being that are different, yes, but not wrong or illegitimate.

If we can learn that, we’ll be able to see the past with fewer prejudices.

Trances

For those of us here in the modern West, there’s something wild about a trance — something deep and dark and unpredictable. It recalls both the primitive and the occult, and is to be regarded at all times with suspicion.

It’s true that trance states can sometimes be abused. The hallmark of a trance is dislocated volition, which is an avenue for others to exert hidden influence over us. But many trances are self-induced and are perfectly safe.

“Trance,” says Dennis Weir in a book of the same name, “is a phenomenon which can be discovered everywhere, and in nearly any social situation, if you know what to look for.”

Some examples to illustrate the point:

- We enter trances during many of our habitual daily activities. Driving, running, showering, and even eating can be done with almost no conscious volition or awareness. Different sports require stronger or weaker trances. Ping pong probably stands out as one of the most trance-inducing sports.

- Listening to music or watching a movie involves a light trance. Even reading — the ability to have one’s thoughts led along by someone else — requires trancelike concentration. Bad grammar, spelling mistakes, and awkward sentence structure will jolt you out of the reading trance, just like a skipping record can ruin a song or a ringing cell phone break the immersion of a movie.

- Dancing can induce a trance, especially with loud/rhythmic music and in the presence of strobing lights, as at a rave.

- Video games can induce very powerful trances — and it’s no coincidence that we lose hours in what feels like the blink of an eye. Somewhat more manipulatively, casinos (slot machines, video poker) are designed to lull visitors into the same kind of trance.

- The ‘battle trance’ is useful for war, and likely a very old part of our evolutionary heritage.

But if these kinds of trances seem normal enough, there’s one kind of trance that stands apart from the others as especially deviant: possession. This is the most difficult kind of trance to learn to see as legitimate — but even here we should be open-minded.

Keith Johnstone explores possession in the last chapter of Impro. For some 40 years he’s been using exaggerated character masks to induce possession in his students. This isn’t a fake act put on by con-artists in order to deceive their marks. It’s something that even a novice student is capable of experiencing in a genuine way.

A common stereotype about possession is that only crazy people are capable of it. But Johnstone argues that this is exactly backwards:

The ability to become possessed is a sign of correct social adjustment. [emphasis mine]

This accords with what we know about hypnosis: that the hypnotee has to be suggestible, that is, responsive to social conditioning. It also accords with what Julian Jaynes says about other patterns of diminished conscious volition: that they require the participant to accept the will of the group (or what he calls the collective cognitive imperative). A person entering a trance needs a lot of trust, both in himself (not to do anything truly out-of-bounds) and in the people he’s with (not to take advantage of him). “Disturbed people censor themselves out,” Johnstone says. “Either they can’t do it, or they’re too afraid to even try.”

Scene from The Exorcist (1973)

And of course possession doesn’t mean that actual spirits take over the body. (Remember: we must never let the interpretation of an experience mislead us into thinking the experience itself is illegitimate.) The spirits are metaphorical, but their effects are very real indeed. Whatever part of the brain is responsible for imagining the spirit really does ‘take over’ from the part that’s normally responsible for conscious volition. If your sensorimotor cortex and speech regions of the brain are typically hooked up to your conscious will, in a possession they are simply rewired to accept inputs from the imagination.

Hallucinations

Hallucinated voices are as real as just about anything. They aren’t what they purport to be — sounds coming from the external world — but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

Maybe. But today I’m going to attempt to portray hallucinations as legitimate — exotic but ultimately sensible.

The first step to legitimacy is realizing that hallucinations are prevalent. A recent survey of 13,000 Europeans found that 27% experienced some kind of daytime hallucination. Estimates for hearing voices are lower, but range from 2% to 15%, and probably between 2% and 4% for habitual hallucinations.

The second step is to understand that hallucinated voices are as real as just about anything. They aren’t what they purport to be — sounds coming from the external world — but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

Let’s count the many ways that hallucinated voices are real:

- They are real neurological patterns that exist in real human brains.

- They are subjectively real. The listener actually hears them.

- They satisfy the criterion for reality put forward by David Deutsch in his book The Fabric of Reality: they kick back. You can read the whole argument here.

- They have metaphorical reality. We can reason about the voices the same way we talk about a movie with our friends (discussing the characters’ motivations, their moral worth, etc.).

- They have real intelligence — because (this is crucial) they’re the products of a bona fide intelligent process. They’re emanating from the same gray matter that we use to perceive the world, make plans, string words together into sentences, etc. The voices talk, say intelligent things, make observations that the hearer might not have noticed, and have personalities (stubborn, encouraging, nasty, etc.). They are, above all, the kinds of things toward which we can take the intentional stance — treating them like agents with motivations, beliefs, and goals. They are things to be reasoned with, placated, ignored, or subverted, but not things whose existence is to be denied.

The final step (in learning to see hallucinations as legitimate conscious experiences) is to note that the voices aren’t necessarily maladaptive. Not all voices are sinister or persecutory. In fact, one of the most common types of hallucinated voice is the one that narrates the listener’s actions in the third person. “She is getting up from her chair.” “She is watching TV.” Such a voice is occasionally insightful, often annoying, but ultimately benign.

Certainly many people who hear voices are truly disturbed, and perhaps some are beyond repair. Even so, it’s hard to isolate the effects of the hallucinations from the effects of (a) other psychosocial problems (including those arising from trauma and abuse) and (b) the treatment people receive once they get diagnosed.

Eleanor Longden

However well-meaning the treatment is, from the patient’s perspective it’s going to come across as persecution. The moment someone admits to hearing voices begins the process of treating her as subhuman and removing her from sane society. It’s hard enough to hear voices in a culture that treats it as a symptom of insanity, but it’s entirely worse to be institutionalized, stripped of your dignity, and treated as a non-person. In the case of hearing voices, the diagnosis can be worse than the disease.

Such was the experience of Eleanor Longden, who gave an eye-opening TED talk about her experiences with hallucinated voices. In college Eleanor started hearing a neutral, impassive narrating voice, but when she finally told a friend about it,

a subtle conditioning process began. The implication that normal people don’t hear voices, and the fact that I did, meant that something was very seriously wrong. Such fear and mistrust was infectious. Suddenly the voice didn’t seem quite so benign anymore. And when my friend insisted that I seek medical attention, I duly complied. [This and subsequent quotes have been lightly edited for print.]

Her experiences with the psychiatric establishment seemed almost designed to aggravate her condition. Her doctors began by ignoring the problems she had experienced out in the world (e.g. childhood abuse). Instead they focused almost exclusively on her hallucinations (to the point of fetishizing them) in order to diagnose her with schizophrenia. She was, in her words, “diagnosed, drugged, and discarded,” and her mental health status became “a catalyst for discrimination, verbal abuse, and physical and sexual assault.”

Through all of this, the voice grew increasingly persecutory:

Having been encouraged to see the voice not as an experience but as a symptom, my fear and resistance towards it intensified. This represented taking an aggressive stance towards my own mind, a kind of psychic civil war. And in turn this caused the number of voices to increase, and grow progressively hostile and menacing.

It was only after two years of this that she learned to start treating the voices as real. Her crucial insight was

that my voices were a meaningful response to traumatic life events, particularly childhood events, and as such were not my enemies, but a source of insight into solvable emotional problems.

I learned to separate out a metaphorical meaning from what I’d previously interpreted to be a literal truth. For example, when voices threatened to attack my home, I learned to interpret it as my own sense of fear and insecurity rather than an actual, objective danger…. And I would thank the voices for drawing my attention to how unsafe I felt, because if I was aware of it, then I could do something positive about it.

I would set boundaries for the voices, and try to interact with them in a way that was assertive yet respectful….

And throughout all of this, what I would ultimately realize was that each voice carried overwhelming emotions which I’d never had an opportunity to process or resolve: memories of sexual trauma and abuse, of anger, shame, and low self-worth. The voices took the place of this pain and gave words to it.

All of this leads, tentatively, to the conclusion that we should treat voices as valid, meaningful subjective experiences, to be analyzed and explored with a posture of openness — rather than as deviant symptoms to be fetishized, marginalized, and suppressed with drugs. Unsurprisingly, this has become something of a social movement (see the Hearing Voices Network).

A final thought

When we accuse a hallucinated voice, or the spirit that takes over during a possession, of being unreal, on what do we base the accusation?

Both voices and spirits are, as we’ve seen, neurologically real — they correspond to a real pattern of neurons capable of exhibiting real intelligence. Both can be treated as agents, i.e., the kind of thing toward which it’s productive to take the intentional stance.

If anything, our objection lies in the fact that voices and spirits don’t have any reality in the world outside our minds.

But there’s something else that has all these properties: the self. I, ego, myself, my conscious will. A neurologically real agent with no physical reality outside of the mind.

Maybe, then, the reason we’re allergic to hallucinated voices and possession-spirits isn’t that they aren’t real, but that they compete with ‘us’ for legitimacy.

![]()

How many agents can take root in one brain? To find out, continue to the next installment of this series, One Brain, Many Selves: Demons, Tulpas, and Neurons Gone Wild.

Have you heard voices or experienced a trance state? Comment below!

Liked this post? Subscribe to my RSS feed to get much more!