How important are psychedelics in the religious experience of the United States? We know drugs like LSD and psilocybin can occasion powerful, life-changing experiences of awe and renewal. We also know psychedelics have been used by millions of people since the 1960s. But no one has ever tried to count the number of people who’ve had psychedelic-related mystical experiences. I ran a survey of over 6,000 people to get an answer.

Background: Walter ‘Wally’ Pahnke and psychedelic mysticism

Fifty-one years ago, a massive 9.2 Richter scale earthquake shook Alaska. At the same time, Wally Pahnke was experiencing another sort of earthquake. It was Good Friday and the Harvard graduate was having his first experience with a high dose of an experimental drug called LSD.

As the drug took effect Pahnke first became aware of his core self — not the usual self that worried about the opinions of others or what-to-eat — but a “core stripped bare of all pretense and falseness,” as he described in a letter. Then Pahnke went somewhere else. There was a white light of absolute purity and cleanness, like a glowing and sparkling flame, so penetrating and intense that it was not possible to look directly at it. Awe, reverence, and sacredness washed over him:

I had the image of going down deep into a dark, silent pool. Then I had a vision of absolute DIVINE love. It was like a flowing spring of silvery white liquid overflowing upward and was very beautiful to watch and feel. The feeling was of love and compassion toward the Divine and toward all men. I had the insight that all men had this same potential and worth within themselves. All men were equal in the sight of God and to my own feelings at this moment. I realized how I had not taken this enough into account in my past actions.

This sort of experience had led Pahnke, a Protestant minister with a medical degree, to design a groundbreaking study of direct religious experience using psychedelics. The study investigated whether an obscure psychedelic called psilocybin could, in the right context, produce genuine mystic experiences of the sort described by Christian visionaries.

To be honest, this was in question only for mainstream Western culture and science. No one familiar with traditional uses of the cactus peyote, the psychedelic mushroom, or the visionary tropical brew ayahuasca could doubt that these substances can facilitate mystical experiences. Years later, in 1979, a group of scholars would propose calling these psychedelics “entheogens,” from generating the divine within, to more accurately and respectfully describe their traditional contexts. But science was not this ethnographically sophisticated in the early 1960s.

For the study, Pahnke and his colleagues recruited twenty religious but drug-naive students from Andover Newton Theological School to be participants. They gathered on April 20, 1962, Good Friday, in a basement chapel at Boston University. As organ music filtered down, half of the participants were given 30 mg psilocybin. The other half received a vitamin (niacin) that caused skin flushing, a ploy the researchers hoped this would fool the students about who had gotten the psychedelic. Rev. Howard Thurman, the chaplain of Boston University and a man who had mentored Martin Luther King, Jr, officiated a three-hour mass, with the sound piped into Marsh Chapel which held a few dozen people, including ten who were feeling increasingly strange.

[pullquotecenter]Fourteen months after the first Hopkins study, more than half of the participants considered the experience among the top five most meaningful spiritual experiences in their lives.[/pullquotecenter]

In his writings, Pahnke emphasized the impressive positive results: Nine of the ten who received psilocybin reported a religious experience (compared to only one in the placebo group). People who had previously studied the Divine now experienced it. Huston Smith, who went on to be a prominent religious scholar, later stated that, until the Good Friday Experiment, he had, “no direct personal encounter with Him/Her/It of the sort that bhakti yogis, Pentecostals, and born-again Christians describe.” Another participant recalled the experience as “a very vivid opening onto another aspect of reality. Here I thought I knew what I was talking about; it was like writing about China and then getting a chance to go there.”

Yet not everyone experienced religious ecstasy. One participant responded particularly badly, having what Pahnke called a “psychotic episode’’ and was given an antipsychotic tranquilizer. Neither Pahnke nor Leary ever wrote about this incident, part of a disturbing pattern of some early psychedelic proponents hiding adverse reactions and methodological flaws. The psychotic episode only came to light when Rick Doblin conducted a follow-up study 25 years later. At that time, the former participant refused to discuss the experience with Doblin, although a colleague opined that they didn’t believe the participant suffered lasting ill effects.

Pahnke died young in a scuba diving accident in 1971. Psychedelics became difficult to study, a casualty of the wider culture wars and a more narrow struggle for the soul of modern psychiatry. Scientific attempts to produce mystical experiences largely halted until the late 1990s when an engineer named Bob Jesse began quietly working to reignite the research. Ultimately partnering with pharmacologist Roland Griffiths, Jesse was able to restart the research at Johns Hopkins in 2002. These studies, run by a team that includes Bill Richards, Matthew Johnson, and Katherine MacLean, have extended Pahnke’s study. They confirm that psychedelics can occasion mystical experiences in spiritually-inclined, previously drug-naïve people. And these experiences are lasting: fourteen months after the first Hopkins study, more than half of the participants considered the experience among the top five most meaningful spiritual experiences in their lives.

From a scientific point of view, many interesting questions remain. One is how often these experiences are produced in people who are not already spiritually inclined and who take the drug in a less meditative, less suggestive setting. It is definitely true that drug-related mystical experiences can happen without any specific preparation. In a study I published in 2010, the mixed psychedelic-entactogen drug MDA produced mystical experiences in a fairly traditional hospital setting devoid of spiritual decor. But my study was too small to give a good estimate of how often mystical experiences happened on psychedelics. The best answer we have may come from a 2011 analysis of psilocybin studies in Franz Vollenweider’s lab in Switzerland. This analysis suggests about 22% of volunteers will have a mystical experience after psilocybin in an ordinary laboratory setting.

My Survey: mystical experiences and potentially “contributing” activities

A natural follow-up question is how common and important these mystical experiences are at the population level. Nationwide surveys tell us 15.1% of the population aged 12 and older in the United States have used psychedelics. Given this widespread use, could psychedelics be a significant part of the religious experience of the U.S? To my knowledge, this question had not yet been addressed by scholars. I decided to try to answer it by conducting a large survey.

Before I began the survey, I did background research on mystical experiences. Mystical or religious experiences turn out to be surprisingly common. (Though the terms “mystical”, “religious”, and “spiritual” have distinct meanings in some fields of study, here I’m using the words essentially interchangeably.) Around 35% have had some moment of sudden religious awakening or insight. These experiences are more common among the religious. A 2009 poll by the Pew Research Center found the numbers run from about 40% for Catholics and mainline Protestants up to about 70% for white evangelicals and black Protestants. Yet experiences aren’t limited to church goers; about 30% of those who are unaffiliated with any particular religion have had a religious experience.

This number used to be lower: polls find the percent of people who say they’ve had a mystical experience has more than doubled since 1962. Given the prevalence of drug use since then, it’s not a stretch to wonder if the drug taking and the mystical experiences are connected.

8 in 1,000 adults have had one or more drug-related mystical experiences — close to and possibly higher than the percent of adults in the U.S. who are Buddhist.

To survey the public, I ran an anonymous online survey using Google Consumer Surveys. Although this tool is new, the Pew Research Center has found that the difference between Google surveys and Pew’s telephone surveys on the same topics is small. And Nate Silver concluded that Google’s surveys in the 2012 presidential election were more accurate than many other surveys.

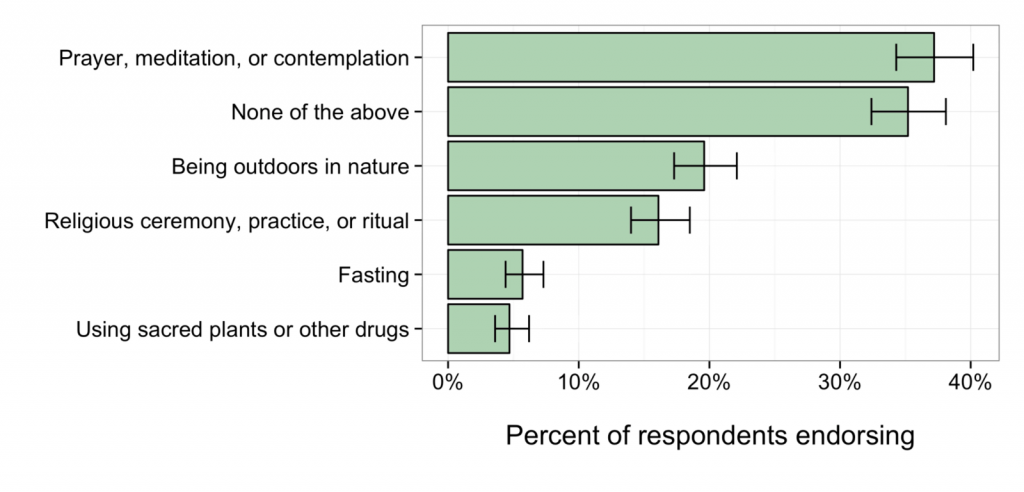

I used only two questions in my survey. The first one was based on that used by past polls. It asked “Have you ever had a ‘religious or mystical experience’ — that is a moment of sudden religious insight or awakening?” People could respond with ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘I don’t know’. Anyone who said yes was given a second question: “Which of the following activities, if any, were you doing immediately before this religious or mystical experience?” Participants could check as many of the following activities as applied: Prayer, meditation, or contemplation; Being outdoors in nature; Religious ceremony, practice, or ritual; Fasting; Using sacred plants or other drugs; or None of the above.

Results

In the end, 6,209 adults from across the U.S. participated. Almost 1 in 5 (19.6%) said they had one or more religious experiences. The most commonly reported activities before the experience were: Prayer, meditation, or contemplation (37.2%); Being outdoors in nature (19.6%); and Religious ceremony, practice, or ritual (16.1%). Less commonly, respondents reported fasting (5.7%) or drug use (4.7%). A large percent (35.2%) reported not engaging in any of these activities before their experiences. The immediate take-away is that mystical experiences are certainly associated with traditional religious activities, but many have “contributing” activities that are not traditionally seen as religious.

Activities done before a mystical experience

One of these potential nontraditional contributing factors is the outdoors. Thirty-three in 1,000 people reported having been outdoors in nature before a mystical-religious experience. Following Maslow’s work in the 1960s, natural environments have been known as a common trigger for peak experiences. Yet the role of nature in mental health and spiritual growth is certainly still understudied.

As for drug use, 8 in 1,000 adults have had one or more drug-related mystical experiences. As a comparison, this is close to and possibly higher than the percent of adults in the U.S. who are Buddhist (which is 7 in 1,000). Over a quarter (26.9%) of those reporting drug use before a mystical experience also reported either prayer or ritual before an experience (not necessarily the same one). These people — roughly 1 in 500 — may have been explicitly using drugs as part of their spiritual practice or were led to spiritual practice as a result of experiences on drugs.

Is this number large enough to explain the doubling of mystical experiences since the 60s? Not directly. But we should not underestimate how a life-transforming experience can ripple out, affecting those around us. Jack Kornfield once claimed that “the majority of Western Buddhist teachers used psychedelics at the start of their spiritual practice.” If psychedelics do encourage a few people to seek and teach, the effects on our society would be large. Those who have experienced the absolute divine love that Pahnke described may well contribute to a culture in which the sacred is more available to more people.

After note: writing up and archiving the data

As an experiment in open science, I am posting a manuscript and the raw data on the site github, which is used by programmers to archive code. There is also a link there for accessing the survey on Google Consumer Surveys, which has a slick interactive interface. I invite you to further analyze the data — there are some neat demographic aspects that I haven’t highlighted. If you use the data in a publication, please cite my github-hosted manuscript:

Baggott, Matthew J. 2015. A brief survey of drug use and other activities preceding mystical-religious experiences. Preprint.https://github.com/mattbaggott/mystical-survey

![]()

This article was originally published on Medium.

Matthew Baggott, PhD, is a data scientist and neuroscientist with over fifteen years experience conducting clinical research on the effects of controlled amounts of psychedelics like MDMA, MDA, and LSD in healthy volunteers.

Liked this post? Subscribe to my RSS feed to get much more!