You may have heard of ESC, the Ethnobotanical Stewardship Council which bills itself as “a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving lives by assuring the sustainability and safe use of traditional plants.” They recently raised over $20,000 in an Indiegogo campaign. Their aims may seem honorable enough, but not everyone is impressed. Below is a scathing condemnation of the ESC’s structure, methods, and plans for the future, signed by a number of academics and other concerned parties. (via PsyPressUK)

Statement Critiquing the Ethnobotanical Stewardship Council (ESC) (*)

We, the academics and other experts undersigned, manifest publically our rejection of the ESC’s methods and goals. The following statement has been made public after more than one year of “dialogues” and correspondence with the ESC, as we do not feel our concerns have been properly addressed.

The information below is a reflection based on the ESC’s reports and materials available online, in podcasts, in public representations and interviews, and from private letters and emails exchanged between us. All the information is supported by actual quotes from these sources, but these have been mostly deleted for the sake of space. The ESC has currently raised over $90,000 in a campaign to introduce ayahuasca use to a market-driven “certification” system based on discourses of “safety” and “sustainability.” We believe that, rather than ensuring the sustainability of ayahuasca and the safety of those who use it, the ESC approach is actually damaging ayahuasca sustainability and practices, and that something urgently needs to be done about this. Our reasons are as follows:

1. Alarmist campaign tactics.

“Ayahuasca’s reputation, habitat, legal standing, and very healing traditions are all at stake.”

In order to justify the need for a certification process, the ESC promotes a fear-based fundraising campaign, implying that the use of ayahuasca results in a high incidence of accidents, rapes and deaths; that the plants are on the verge of disappearing; and that there is a lack of regulation. Strategies have included using video of a rape victim demanding that something be done alongside an affirmation that the ESC is doing something, and implying that the ESC is involved in scientific research and treatment of people with ayahuasca when it is not. While there are certainly emerging safety issues that require an informed response, the overall scope of concern is greatly exaggerated. Further, the proposed ESC “intervention” is disproportionate to the evidence currently available on any of these issues.

2. Claims that lack of safety, breakdown of traditional means of control, and lack of regulations might cause governments in South America to forbid the use of ayahuasca.

There are no governments in Amazonian South America thinking of forbidding ayahuasca use: the discourse on health and safety is largely a foreign and imported one. Traditionally, ayahuasca is considered an “traditional indigenous medicine” or “a spiritual doctrine” and a legitimate expression of native knowledge or religious freedom. There are many traditional, bottom-up, community-based means of regulation in the Amazon that already exist and function. There are also more formal means of control in some places, such as the regulations in place in Brazil, Peru, Colombia, etc.

3. Lack of indigenous representation.

The ESC claims to include all voices in a “dialogue.” There actually is no indigenous representation at all, and even if there was, the question of who has the right to represent others is extremely problematic, as leadership in the communities in question is a collective process.

There are also no experts involved who have substantial experience with specific indigenous groups, no Amazon-based NGOs or institutions, nor any with close historical ties to any particular community. Furthermore, nothing has been translated into Spanish or Portuguese, let alone any of the indigenous languages of non-English speaking “stakeholders”; the website, the “Ayahuasca Dialogues” report, and the “Health Guide” are all only available in English.

The claims that this project is a “bottom-up” initiative implies that it arises organically from local people acting upon issues important to their endeavors, and in line with their own philosophies. In reality, this is a Western-oriented, top-down initiative, in the mold of naïve development projects that have caused irrevocable damage to traditional and rural communities. An intervention on the scale the ESC plans demands a full impact assessment before anything is done.

4. Promoting safety, “cleaning up sorcery,” and certifying ayahuasca retreat centers and shamans.

The ESC has publicly claimed that it will be “making sure people are not getting witchcraft put on them,” and reveals no understanding of nor cultural sensibility towards the importance of secrecy, sorcery, and invisibility, nor regarding informal, social and traditional means of control. Sorcery is – among other things – a form of local regulation where inequality and jealousy may drive sorcery accusations. The ESC intends to replace the “morally ambiguous” complex of healing/sorcery in Amazonia with market regulations. “Stewarding” ayahuasca, by certifying centers in the same way that producers of forest products are certified, is wholly inappropriate for indigenous shamanism.

Indigenous cosmologies also conceptualize disease and health differently. The ESC project to “modernize” and “sanitize” indigenous uses of ayahuasca threatens to create an unnecessary and Western-imposed bureaucratization and professionalization/institutionalization of traditional medicine. Those centers that do not want to adopt outside interventions and norms would be uncertified vis-á-vis those that do, and this creates a discriminatory trend.

5. Market orientation, commercial language, and promotion of ayahuasca tourism.

The ESC’s aesthetics and vocabulary derive from a neoliberal market-based framework, employing such terms and concepts as “incentives,” “cost-effective,” “competitiveness,” “willingness to pay,” “value chain,” “stakeholder,” etc. We assert that all ayahuasca practices have operated outside of a Western market-driven approach in the past, and that currently Westerners are not the only ayahuasca participants.

The ESC maintains that all indigenous villages in the Amazon should be given the chance to develop ayahuasca tourism, and that ayahuasca tourism, capitalism, and development are perfectly compatible. Further, it assumes that promoting ayahuasca seekers’ trips to the Amazon will not exacerbate the economic inequalities that already exist in the Amazonian context. We disagree profoundly, and we do not see that the ESC’s neoliberal project is either pertinent or necessary, from the perspective of those natives of the Amazon who will be affected. Such an approach will necessarily damage the organic local contexts and philosophies that have thrived for many centuries outside of Western demands, dominance, and impositions.

6. Alleged conservation and protection of ayahuasca plants and admixtures in order to avoid their disappearance.

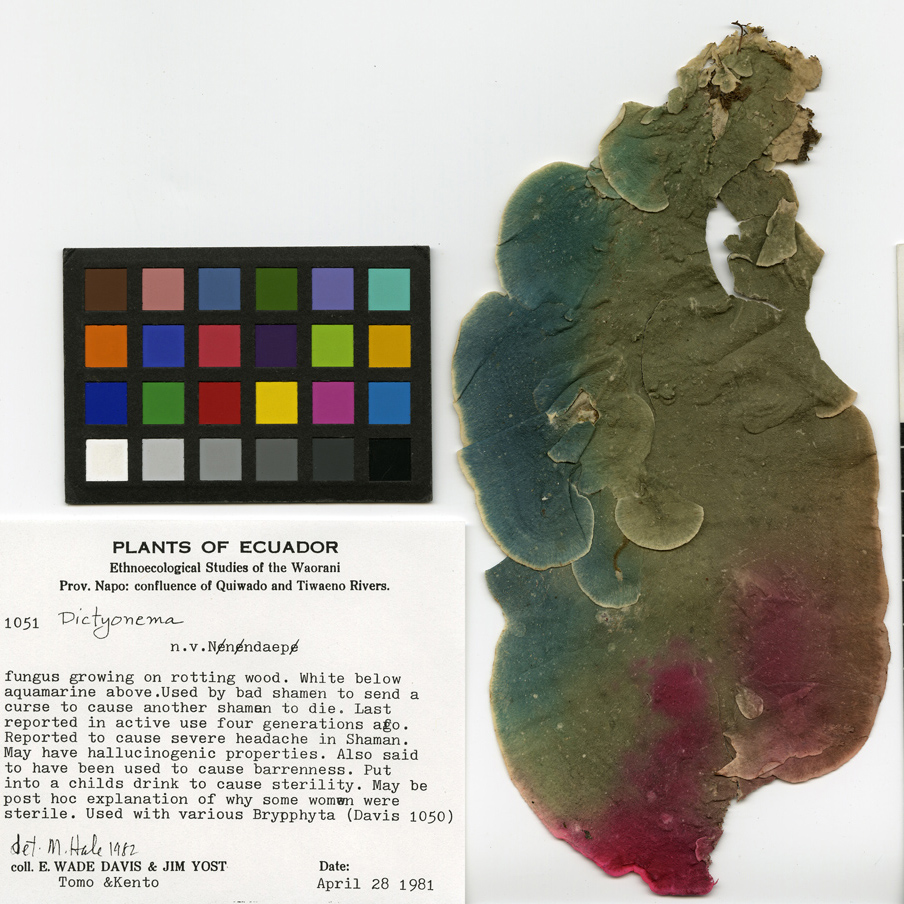

The ESC has claimed that ayahuasca plants are in danger of disappearing due to consumption and commerce, and that ESC will ensure their conservation. Neither Banisteriopsis caapi nor Psychotria viridis are placed under the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Both are planted throughout Brazil, and in vibrant new ayahuasca scenes in other countries and continents. There are similar initiatives in the Peruvian Amazon, where several botanical gardens collecting diverse species also exist, as well as small yagé and chagropanga planting projects in Colombia, and home gardens in Ecuador.

Also, it is important to remember that there are traditional circuits of plant exchange that outside initiatives could disrupt. In sum, all this involves profound and complex intercultural issues. The major forces responsible for the devastation of the Amazon are the lumber industry, agricultural enterprises, big pharmaceutical companies, and international patterns of material consumption, rather than the individual consumption of or trade in ayahuasca.

Despite the name, the ESC has no expertise in ethnobotany, is not engaged in university research, shows little familiarity with ongoing scientific research in these areas, and has no concrete plans to promote the conservation or biodiversity of ayahuasca. Ayahuasca is unlike other medicinal plant commodities; it is fundamentally embedded into shamanistic healing traditions, which are in turn part of complex ritual and symbolic systems throughout South America.

7. Lack of scientific evidence and rigor.

For example, the ESC has repeatedly announced that 100,000 visit the Amazon per year for ayahuasca, without providing any solid evidence for this claim. This dubious estimate is marshalled to support a fear-based, urgent fund-raising campaign. The “Health Guide” and the “Dialogues Report,” frequently quoted publically as sources of information, are not created by accredited experts, are full of factual inaccuracies, and bring nothing new to the public debate. They are promotional materials, which are used to justify the existence of the ESC.

8. Problematic representation of expertise in the field.

The ESC gives lectures and media interviews around the world as an “expert institution,” but they have not consolidated the expert advice offered, and seem unaware of existing debates; nor has their staff conducted any substantial Lowland South American fieldwork. There is also a clear ignorance of basic anthropological, sociological, and other factors pertinent to the Amazon region. The ESC’s participation in psychedelic conferences and community forums are largely platforms for fundraising.

9. Changing discourse, lack of clear plans, unrealistic goals.

Despite the strong fundraising, media visibility, and rhetoric, the ESC appears confused about its mission, focus, scope, and orientation – what it wants to do and how. The ESC has a chameleon-like nature. Its strategy for “dialogue” is to co-opt and incorporate criticisms, without actually effecting substantial changes. Affirmations made publically have afterwards been denied, such as the claim to be able to protect people from witchcraft; or they are “previous plans, now abandoned,” evidencing their lack of clarity.

The scope of the ESC covers conservation, policy and regulation in Peru and beyond, anti-sorcery measures, promoting development, facilitating ethno-medical tourism and pilgrimage, ensuring safety and fair distribution of foreign income, assessing what went wrong in accidents, implementing grieving mechanisms, preventing sexual abuse, surveying participants, and certifying centers in different cities and villages throughout Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. They plan to extend the methods and models to iboga and peyote, and possibly to marijuana, kratom, kava, and psilocybin mushrooms. These claims are huge, unrealistic, and deeply problematic.

10. Lack of transparency about financial benefits.

It is not clear what the charges will be for certification or other services, if there will there be voluntary donations from lodges and providers, and how this will be turned into staff wages and funds to run the organization itself. While ESC is a non-profit organization, it still needs wages to operate and projects need to be defined as important and viable so as to justify their infrastructure. There are also no public reports on how public donations have been used thus far.

11. Rhetoric around the idea of “dialogue” and “community.”

The ESC affirms that it is “community-based,” “grew out of community concerns,” is based on “voluntary participation,” and promotes a “dialogue.” This is empty rhetoric, which does not resonate with experts, nor with indigenous local people. ESC remains unresponsive to concerns regarding how the “stamp of approval” will harm the villages and centers that are not interested in replicating their ideas. The ESC’s lack of on-the-ground experience is apparent, the ethnocentricity of the project is alarming, and the assumption that they know better than the locals how to manage ayahuasca is unfounded.

The ESC does not consist of an appropriate number of experts in the field, nor locally-based Amazonian leaders. None of the founding board members live in the Amazon, nor have they any long-term experience in the field. The Executive Director tried ayahuasca for the first time in 2013, and has very little experience with it. Furthermore, the ESC has repeatedly rejected expert advice, describing groups of long-term experts in the field offering sustained opposition as a “vocal minority.” Add to this “vocal minority” the roster of scientists and locally knowledgeable people who have, from the outset, refused to legitimize the ESC’s naïve plan with their support, as well as all of those advisors who left the organization alarmed at what they saw, and one can safely conclude that it is the ESC who is the vocal minority.

12. Misappropriation of the voice of ayahuasca.

The ESC implies that it represents ayahuasca directly, with tweets such as “Now is the time to give back to ayahuasca.” But does it?

Conclusion

The mission, to “transform the lives of people all along the ayahuasca value chain, from the people who drink ayahuasca all the way to the people who cultivate and offer ceremonies” is extremely problematic on many levels. Our lack of support for the ESC does not reflect our unwillingness to discuss facts; rather, it stems from extensive discussion with the ESC, and reflects our concerns that ESC will adversely affect communities in the pursuit of its ill-conceived goals.

The fundamental question remains: What mandate do they have to impose Western, hegemonic, neoliberal norms upon communities in Latin America of which they do not have a detailed understanding?

We urge the staff to direct their skills towards educating foreigners who are interested in ayahuasca, and leave the stewardship of ayahuasca to those with generations of expertise behind them.

December 21st, 2014. Signed:

Brian Rush, PhD, U. of Toronto, Project Leader Ayahuasca Treatment Outcome Project (ATOP)

Bia Labate, PhD in Anthropology, NEIP, Ayahuasca researcher, Brasil/Mexico

Daniela Peluso, PhD in Socio-cultural Anthropology, Amazonian specialist

Danny Nemu, BsC, Psychedelic Press UK

Clancy Cavnar, PySD, NEIP, co-editor of “Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond”

Alex Gearin, PhD Candidate in Anthropology University of Queensland, Australia

Matthew Meyer, PhD in Anthropology, NEIP

Dena Sharrock, PhD Candidate in Anthropology University of Newcastle, Australia

Brian Anderson, MD, MSc, University of California San Francisco, NEIP

Marcelo Mercante, PhD in Anthropology, NEIP, Ayahuasca researcher, Brazil

Celina De Leon, Posada Natura Costa Rica and ATOP

Stanley Kripper, PhD Saybrook University, Oakland, California

Eleonora Molnar, MA, Canada

Anja Loizaga-Velder, Dr. sc. hum., Nierika AC, ATOP, Mexico

Gretel Echázu, PhD Candidate in Anthropology University of Brasília, NEIP

Alhena Caicedo, PhD in Anthropology University of los Andes, Colombia

Edward MacRae, PhD, ABESUP, NEIP, CETAD, UFBA, Brazil

Rush, Brian et. al (Dec 21, 2014). Statement Critiquing the Ethnobotanical Stewardship Council (ESC). Núcleo de Estudos Interdisciplinares sobre Psicoativos – NEIP. Available in: http://www.neip.info/html/objects/_downloadblob.php?cod_blob=1568

![]()

What do you make of this open letter? Fair assessment, or overreaction? If you’re a current supporter of the ESC, does this make you think twice or strengthen your resolve? Leave your thoughts in the comments!

Liked this post? Subscribe to my RSS feed to get much more!