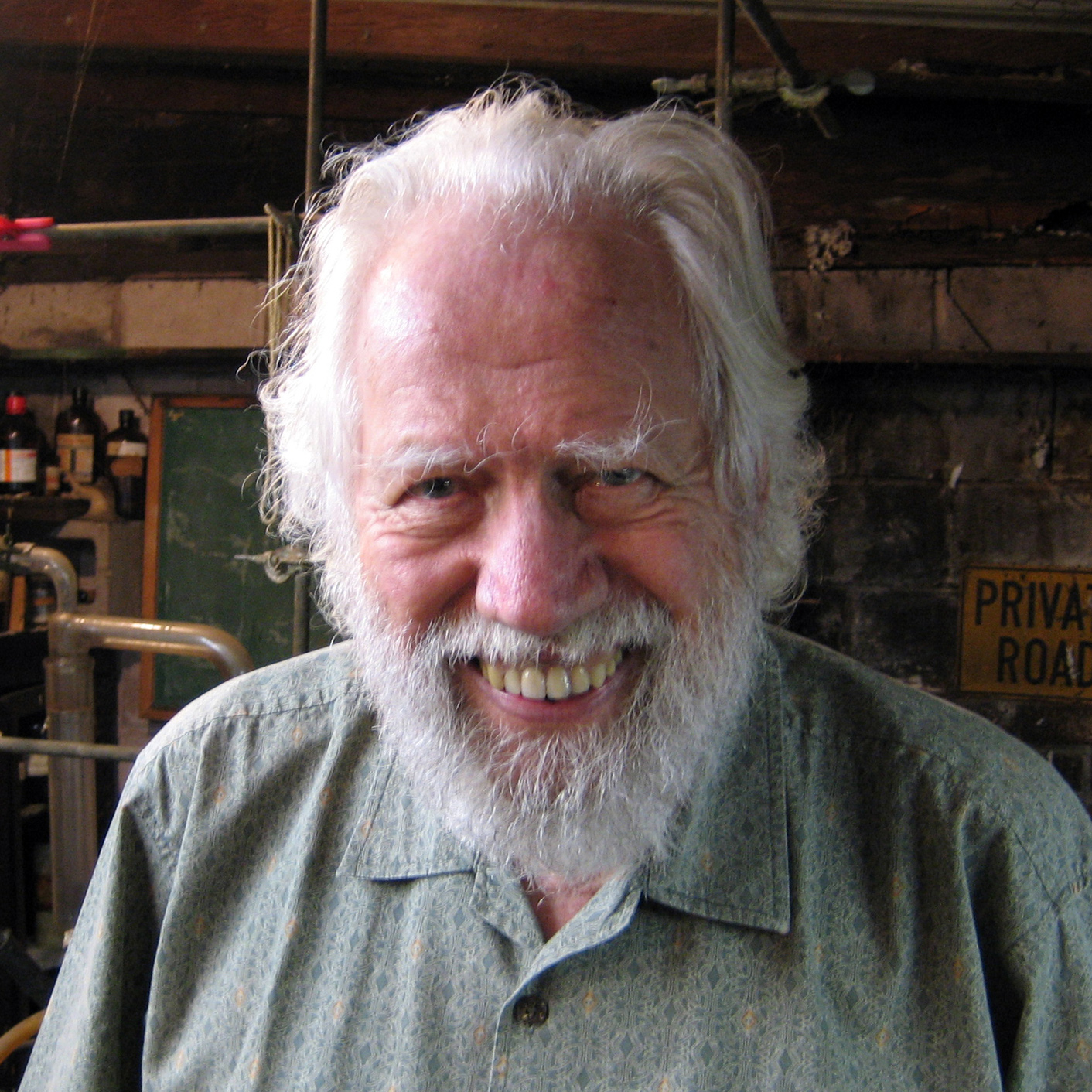

Dr. Alexander Shulgin, the influential and beloved psychedelic pioneer, has passed away at the age of 88. He died of liver cancer on Monday, 2 June, surrounded by family and friends at his home in California. Shulgin had suffered declining health in the past few years, including a stroke and the onset of dementia beginning in 2010. About his final days, his wife Ann wrote:

Dr. Alexander Shulgin, the influential and beloved psychedelic pioneer, has passed away at the age of 88. He died of liver cancer on Monday, 2 June, surrounded by family and friends at his home in California. Shulgin had suffered declining health in the past few years, including a stroke and the onset of dementia beginning in 2010. About his final days, his wife Ann wrote:

Sasha knows that he’s dying, but that doesn’t bother him. He doesn’t know he has cancer of the liver, and there’s no need for him to know; that knowledge would give him nothing useful. After all, as he has said, “We all have to die of something!”

Thanks to all of you for your support all these years. We appreciate every single dollar and every note or e-mail. You have kept our Tibetan and British caregivers here with him, and he has been surrounded by love and a lot of laughter, due to your help and compassion.

The Shulgin Legacy

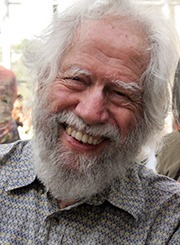

Alexander, or “Sasha” Shulgin, was famous for discovering, synthesizing, and personally testing hundreds of novel psychoactive drugs. He and his wife, Ann — a psychedelic therapist, speaker, and author in her own right — regularly tried new compounds from Sasha’s lab. If, after considerable self-experimentation, a compound proved worthy of further analysis, they would share it with a group of close friends. The “research group” would test the new chemical and rate it for duration, psychedelic qualities, and other effects.

But Sasha always dosed himself first, starting with very low doses to minimize the risk of toxicity. Ann once estimated that her husband had tripped around 4,000 times in his life — that’s more than once a week for over 40 years!

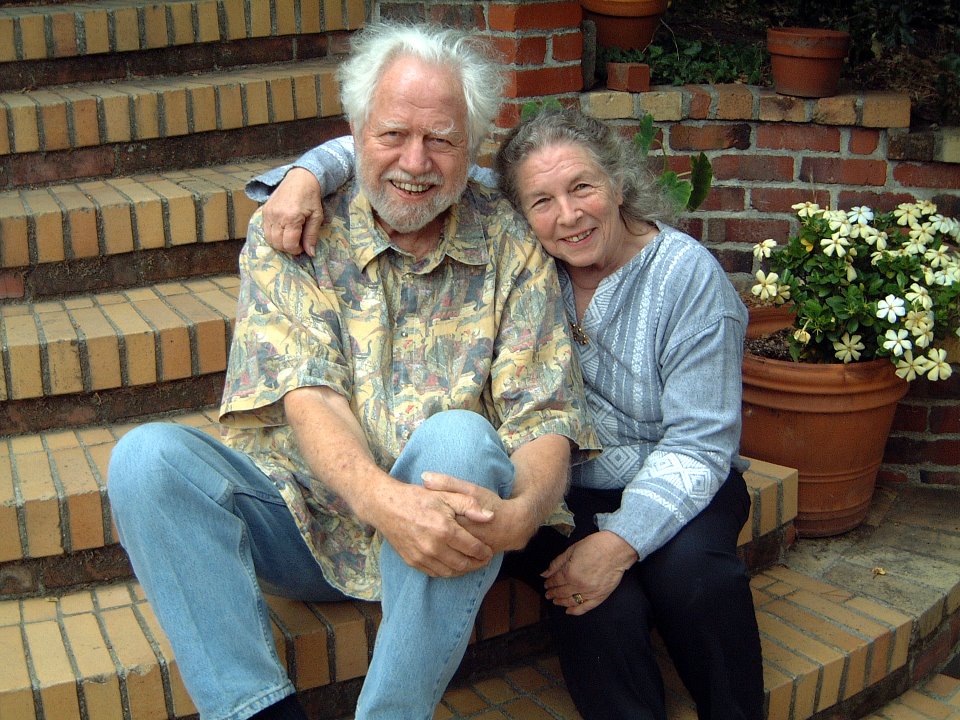

Sasha and Ann Shulgin

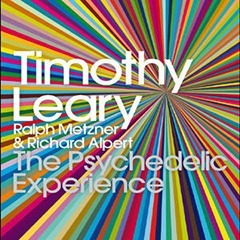

The Shulgins published the results of their research in two groundbreaking volumes, PiHKAL and TiHKAL. The titles stand for Phenethylamines and Tryptamines I Have Known and Loved. For chemistry novices, the tryptamines are a chemical family including LSD, DMT, and psilocybin; phenethylamines include mescaline, MDMA, 2C-B, and MDA. Both classes contain many psychedelic compounds — Shulgin’s specialty.

The volumes, self-published in 1991 and 1997, employ a similar format. Each of the 800-plus page tomes is split into two parts — half autobiography, detailing the couple’s personal love story, and half cookbook, with step-by-step synthesis instructions and subjective impressions of each drug’s effects. (TiHKAL and PiHKAL have little in the way of pharmacology; chemists and others who require a more thorough account of the compounds should look to The Shulgin Index.)

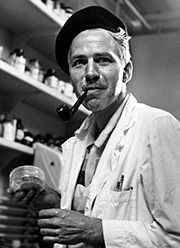

Shulgin’s early days, working for Dow Chemical

The Shulgins believed that information about psychedelic drugs should be freely available, so the chemical overview sections of PiHKAL and TiHKAL have been published online (here and here). As Sasha once put it, everyone has “the license to explore the nature of his own soul.” Only the autobiographical first halves are fully copyrighted; for those sections, you must buy the books. As testament to the couple’s goal of free public access to information, even Sasha’s lab notebooks are being published online at Erowid, with test subject names removed for their protection. You are invited to donate to help Erowid scan the Shulgins’ large collection of valuable documents and share them with the public.

The influence of these books, together with Shulgin’s many scientific papers, cannot be overstated. He was an open-source chemist, freely sharing the synthesis steps for the hundreds of new compounds that he created. His methods focused on easily obtainable precursors, presumably to help underground chemists replicate his work. Shulgin’s synthesis of MDMA, for example, is still widely used.

The drug world has been watching. Within weeks of publishing the chemical synthesis for a new compound, it would appear for sale, often produced by some grey-market lab in China and bought by eager psychonauts around the world. And then, of course, the DEA would ban it, and a new breed of chemicals would emerge, often inspired by another Shulgin publication. For decades, chemists, drug users, legislators, and enforcement officials all watched closely as new compounds churned out of Sasha’s lab.

The Shulgin Rating Scale

Shulgin devised a simple rating system, now known as the Shulgin Rating Scale, for evaluating psychedelic experiences. One of his many contributions to psychedelic science and literature, the Shulgin Rating Scale is now widely used in “trip reports” posted on Erowid and elsewhere to indicate the intensity and nature of a particular drug experience. In PiHKAL, he described the scale in detail:

- PLUS / MINUS (+/-) The level of effectiveness of a drug that indicates a threshold action. If a higher dosage produces a greater response, then the plus/minus (+/-) was valid. If a higher dosage produces nothing, then this was a false positive.

- PLUS ONE (+) The drug is quite certainly active. The chronology can be determined with some accuracy, but the nature of the drug’s effects are not yet apparent.

- PLUS TWO (++) Both the chronology and the nature of the action of a drug are unmistakably apparent. But you still have some choice as to whether you will accept the adventure, or rather just continue with your ordinary day’s plans (if you are an experienced researcher, that is). The effects can be allowed a predominant role, or they may be repressed and made secondary to other chosen activities.

- PLUS THREE (+++) Not only are the chronology and the nature of a drug’s action quite clear, but ignoring its action is no longer an option. The subject is totally engaged in the experience, for better or worse.

- PLUS FOUR (++++) A rare and precious transcendental state, which has been called a ‘peak experience’, a ‘religious experience,’ ‘divine transformation,’ a ‘state of Samādhi’ and many other names in other cultures. It is not connected to the +1, +2, and +3 of the measuring of a drug’s intensity. It is a state of bliss, a participation mystique, a connectedness with both the interior and exterior universes, which has come about after the ingestion of a psychedelic drug, but which is not necessarily repeatable with a subsequent ingestion of that same drug. If a drug (or technique or process) were ever to be discovered which would consistently produce a plus four experience in all human beings, it is conceivable that it would signal the ultimate evolution, and perhaps the end, of the human experiment.

Sasha’s Creations

Everyone has “the license to explore the nature of his own soul.”

The 2C-x family has become particularly influential due to its NBOMe derivatives, in particular 25I-NBOMe (derived from 2C-I) which is often sold as LSD due to its similar effects and duration (though, it must be noted, not a similar safety profile). The importance of these chemicals is not exclusive to recreation, spiritual self-exploration, and therapy — neurologists have studied a radiolabeled form of 25C-NBOMe, derived from 2C-C, for potential use in PET scans to map the distribution of serotonin receptors in the human brain.

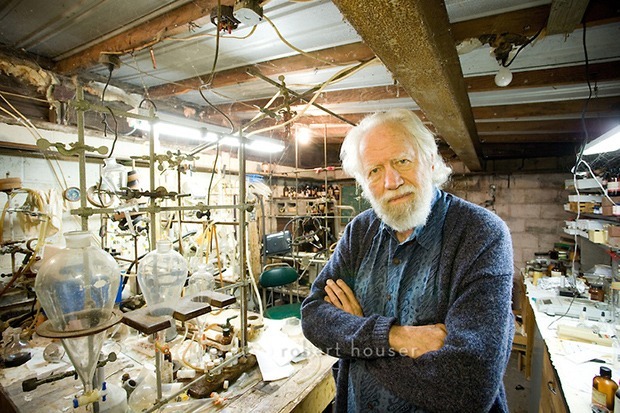

Sasha in his lab. (Photo by Robert Houser.)

DiPT, another of Shulgin’s creations, is unique among tryptamines in that it primarily affects the user’s sense of sound. Unlike most psychedelics, it has little to no visual activity. The effect on the user’s hearing is described as flanging, with a non-linear shift of pitches that renders all music disharmonious. At higher doses of DiPT, all perceived pitches are shifted sharply downward.

That’s not the only unusual entry in Shulgin’s laundry list of discoveries. In a VICE article, Hamilton Morris writes:

His creation 2C-SE was the first and only psychoactive drug to feature the element selenium. He pioneered heavy psychoactive drugs with beta-D, his successful attempt to alter the activity of mescaline via the substitution of deuterium for hydrogen atoms in the molecule’s beta position. Beyond these carefully planned investigations, his curiosity led him to the serendipitous discovery of many new types of drugs he could have never anticipated: extreme time dilation from 2C-T-4, tactile hallucination from 2,N,N-TMT, an unexpected fugue state from 4-desoxymescaline, and the still unclassifiable effects of 5-MeO-pyr-T.

The “Godfather of Ecstasy”

Shulgin is also credited with popularizing MDMA (commonly called ecstasy) among psychologists for use in personal therapy, indirectly leading to its immense popularity as a recreational drug. Merck had patented MDMA back in 1912, but it had been largely forgotten. After a student turned him on to the little-known drug in 1976, Shulgin introduced it to Leo Zeff, the underground psychedelic therapist profiled in The Secret Chief Revealed.

Zeff was so taken with the experience that he came out of retirement, traveling around the US and Europe in order to train hundreds of other psychologists in MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. It quickly gained a reputation among therapists as an impressive catalyst for emotional openness, with patients often showing more progress in a single session than in years of traditional talk therapy.

[pullquotecenter]Know what you’re using, decide just why you’re using it, and you can have a rich experience. They’re not addictive, and they’re certainly not escapist, either, but they’re exceptionally valuable tools for understanding the human mind, and how it works.[/pullquotecenter]

In 1978, Sasha published the first paper publicly describing the effect of MDMA on humans, coauthored with chemist David Nichols. Nichols has since become known as the leading expert on psychedelic pharmacology, having investigated 25I-NBOMe among many other psychedelic compounds related to Shulgin’s work.

In the 1980s, of course, ecstasy became a hugely popular recreational drug. In spite of being outlawed in 1985, it has remained popular ever since, though today it is often called Molly or Mandy. MAPS, the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies, is now investigating MDMA-assisted therapy as a potential cure for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, as well as a potential treatment for social anxiety in autistic adults. MAPS President Rick Doblin estimates that by 2021, MDMA will be approved as a treatment for PTSD. It is hard to imagine any of this coming to fruition if Alexander Shulgin had not plucked this little-chemical from history and dusted it off back in 1976.

Learn More

For a more complete account of Sasha’s life, check out the excellent New York Times article, Dr. Ecstasy, published in 2005. Erowid also has a great collection of interviews, articles, and other odds and ends from Sasha’s life.

Hamilton Morris of VICE visited the Shulgins at their home in 2010, and wrote a poignant article called The Last Interview with Alexander Shulgin. The video version, Shulgins I Have Known and Loved, is well worth 20 minutes of your time:

Hamilton’s voiceover sums it up nicely:

I sat looking at and possibly ogling Shulgin, and thought about the superhuman influence his work has had on the world. The hundreds of deaths, millions of freakouts, tens of billions of dollars exchanged of which he has not received a dime, cumulative millennia of prison sentences, trillions of transformative experiences, decaliters of joy tears, decibels of laughter, and so forth. I wanted to tell him how much he’s changed my life, but I wouldn’t be capable of giving him enough thanks.

I’ll close with a few of Sasha’s own words. Reflecting upon his first psychedelic trip — on mescaline, back in 1960 — he realized that everything he experienced that day “had been brought about by a fraction of a gram of a white solid, but that in no way whatsoever could it be argued that these memories had been contained within the white solid. . . I understood that our entire universe is contained in the mind and the spirit. We may choose not to find access to it, we may even deny its existence, but it is indeed there inside us, and there are chemicals that can catalyze its availability.”

Shulgin was always careful not to prioritize the chemicals over human beings. “Drugs don’t do things,” he said. “They only catalyze what’s already there. No drug has skill. It’s you who has skill. You only have to know it.”

Lastly, an excerpt from PiHKAL that has inspired my own stance on psychedelics:

Use them with care, and use them with respect as to the transformations they can achieve, and you have an extraordinary research tool. Go banging about with a psychedelic drug for a Saturday night turn-on, and you can get into a really bad place, psychologically. Know what you’re using, decide just why you’re using it, and you can have a rich experience. They’re not addictive, and they’re certainly not escapist, either, but they’re exceptionally valuable tools for understanding the human mind, and how it works.

How have Alexander Shulgin’s discoveries affected your life? Leave a comment below.

Liked this post? Subscribe to my RSS feed to get much more!