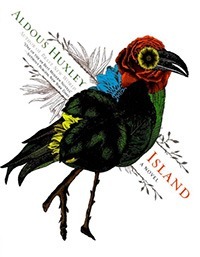

One of my favorite books is Island by Aldous Huxley, a book often prized by psychonauts and others who enjoy looking at society from the outside in. In Island, Huxley lays out the structure for an ideal society while making piercing criticisms of modern Western culture.

One of my favorite books is Island by Aldous Huxley, a book often prized by psychonauts and others who enjoy looking at society from the outside in. In Island, Huxley lays out the structure for an ideal society while making piercing criticisms of modern Western culture.

As the title indicates, Huxley’s utopia is set on a small island, far removed from modern technology and divisive global politics. Some have criticized the book’s characterization and plot, but in Island these are secondary. This book’s main strength is in elaborating a great thinker’s vision of a truly civilized society.

I want to share a couple excerpts of this remarkable book with you. If I mentioned every noteworthy line, I’d end up reprinting the whole book, so I’ll limit myself to a couple highlights.

Dope or Medicine?

In this scene, two Westerners, Murugan and Will, are interacting with two natives of the Island utopia, Dr Robert and Vijaya. Dr. Robert is trying to get the foreigners to understand the value of the local “moksha-medicine” — psilocybin mushrooms — and the mystical experience it produces. The Western visitors, unable to consider the medicine as anything but an intoxicant, refer to the psychedelic mushrooms as “dope.” The doctor is ready with a reply (page 165):

“What’s in a name?” said Dr. Robert, with a laugh. “Answer, practically everything. Having had the misfortune to be brought up in Europe, Murugan calls it dope and feels about it all the disapproval that, by conditioned reflex, the dirty word evokes. We, on the contrary, give the stuff good names—the moksha-medicine, the reality revealer, the truth-and-beauty pill. And we know, by direct experience, that the good names are deserved. Whereas our young friend here has no firsthand knowledge of the stuff and can’t be persuaded even to give it a try. For him, it’s dope and dope is something that, by definition, no decent person ever indulges in.”

“What does His Highness say to that?” Will asked.

Murugan shook his head. “All it gives you is a lot of illusions,” he muttered. “Why should I go out of my way to be made a fool of?”

“Why indeed?” said Vijaya with good-humored irony. “Seeing that, in your normal condition, you alone of the human race are never made a fool of and never have illusions about anything!”

“I never said that,” Murugan protested. “All I mean is that I don’t want any of your false samadhi.”

“How do you know it’s false?” Dr. Robert enquired.

“Because the real thing only comes to people after years and years of meditation and tapas and . . . well, you know—not going with women.”

[This is the] experience that you get with the moksha-medicine, or through prayer and fasting and spiritual exercises. Even if it doesn’t refer to anything outside itself, it’s still the most important thing that ever happened to you.

“Murugan,” Vijaya explained to Will, “is one of the Puritans. He’s outraged by the fact that, with four hundred milligrams of moksha-medicine in their bloodstreams, even beginners—yes, and even boys and girls who make love together—can catch a glimpse of the world as it looks to someone who has been liberated from his bondage to the ego.”

“But it isn’t real,” Murugan insisted.

“Not real!” Dr. Robert repeated. “You might as well say that the experience of feeling well isn’t real.”

“You’re begging the question,” Will objected. “An experience can be real in relation to something going on inside your skull but completely irrelevant to anything outside.”

“Of course,” Dr. Robert agreed.

“Do you know what goes on inside your skull, when you’ve taken a dose of the mushroom?”

“We know a little.”

“And we’re trying all the time to find out more,” Vijaya added.

“For example,” said Dr. Robert, “we’ve found that the people whose EEG doesn’t show any alpha-wave activity when they’re relaxed aren’t likely to respond significantly to the moksha-medicine. That means that, for about fifteen percent of the population, we have to find other approaches to liberation.”

“Another thing we’re just beginning to understand,” said Vijaya, “is the neurological correlate of these experiences. What’s happening in the brain when you’re having a vision? And what’s happening when you pass from a premystical to a genuinely mystical state of mind?”

“Do you know?” Will asked.

It was much more real than what you call reality. More real than what you’re thinking and feeling at this moment. More real than the world before your eyes.

“‘Know’ is a big word. Let’s say we’re in a position to make some plausible guesses. Angels and New Jerusalems and Madonnas and Future Buddhas—they’re all related to some kind of unusual stimulation of the brain areas of primary projection— the visual cortex, for example. Just how the moksha-medicine produces those unusual stimuli we haven’t yet found out. The important fact is that, somehow or other, it does produce them. And somehow or other, it also does something unusual to the silent areas of the brain, the areas not specifically concerned with perceiving, or moving, or feeling.”

“And how do the silent areas respond?” Will enquired.

“Let’s start with what they don’t respond with. They don’t respond with visions or auditions, they don’t respond with telepathy or clairvoyance or any other kind of parapsychological performance. None of that amusing premystical stuff. Their response is the full-blown mystical experience. You know—One in all and All in one. The basic experience with its corollaries— boundless compassion, fathomless mystery and meaning.”

“Not to mention joy,” said Dr. Robert, “inexpressible joy.”

“And the whole caboodle is inside your skull,” said Will. “Strictly private. No reference to any external fact except a toadstool.”

“Not real,” Murugan chimed in. “That’s exactly what I was trying to say.”

“You’re assuming,” said Dr. Robert, “that the brain produces consciousness. I’m assuming that it transmits consciousness. And my explanation is no more farfetched than yours. How on earth can a set of events belonging to one order be experienced as a set of events belonging to an entirely different and incommensurable order? Nobody has the faintest idea. All one can do is to accept the facts and concoct hypotheses. And one hypothesis is just about as good, philosophically speaking, as another. You say that the moksha-medicine does something to the silent areas of the brain which causes them to produce a set of subjective events to which people have given the name ‘mystical experience.’ I say that the moksha-medicine does something to the silent areas of the brain which opens some kind of neurological sluice and so allows a larger volume of Mind with a large ‘M’ to flow into your mind with a small ‘m.’ You can’t demonstrate the truth of your hypothesis, and I can’t demonstrate the truth of mine. And even if you could prove that I’m wrong, would it make any practical difference?”

Maybe it is private and there’s no unitive knowledge of anything but one’s own physiology. Who cares? The fact remains that the experience can open one’s eyes and make one blessed and transform one’s whole life.

“I’d have thought it would make all the difference,” said Will.

“Do you like music?” Dr. Robert asked.

“More than most things.”

“And what, may I ask, does Mozart’s G-Minor Quintet refer to? Does it refer to Allah? Or Tao? Or the second person of the Trinity? Or the Atman-Brahman?”

Will laughed. “Let’s hope not.”

“But that doesn’t make the experience of the G-Minor Quintet any less rewarding. Well, it’s the same with the kind of experience that you get with the moksha-medicine, or through prayer and fasting and spiritual exercises. Even if it doesn’t refer to anything outside itself, it’s still the most important thing that ever happened to you. Like music, only incomparably more so. And if you give the experience a chance, if you’re prepared to go along with it, the results are incomparably more therapeutic and transforming. So maybe the whole thing does happen inside one’s skull. Maybe it is private and there’s no unitive knowledge of anything but one’s own physiology. Who cares? The fact remains that the experience can open one’s eyes and make one blessed and transform one’s whole life.” There was a long silence. “Let me tell you something,” he resumed, turning to Murugan. “Something I hadn’t intended to talk about to anybody. But now I feel that perhaps I have a duty, a duty to the throne, a duty to Pala and all its people—an obligation to tell you about this very private experience. Perhaps the telling may help you to be a little more understanding about your country and its ways.” He was silent for a moment; then in a quietly matter-of-fact tone, “I suppose you know about my wife,” he went on.

His face still averted, Murugan nodded. “I was sorry,” he mumbled, “to hear she was so ill.”

With four hundred milligrams of moksha-medicine in their bloodstreams, even beginners can catch a glimpse of the world as it looks to someone who has been liberated from his bondage to the ego.

He was silent, and Will suddenly became aware of the squeak and scrabble of caged rats and, through the open window, the babel of tropical life and the call of a distant mynah bird. “Here and now, boys. Here and now …”

“You’re like that mynah,” said Dr. Robert at last. “Trained to repeat words you don’t understand or know the reason for, ‘It isn’t real. It isn’t real.’ But if you’d experienced what Lakshmi and I went through yesterday you’d know better. You’d know it was much more real than what you call reality. More real than what you’re thinking and feeling at this moment. More real than the world before your eyes. But not real is what you’ve been taught to say. Not real, not real.'” Dr. Robert laid a hand affectionately on the boy’s shoulder. “You’ve been told that we’re just a set of self-indulgent dope takers, wallowing in illusions and false samadhis. Listen, Murugan—forget all the bad language that’s been pumped into you. Forget it at least to the point of making a single experiment. Take four hundred milligrams of moksha-medicine and find out for yourself what it does, what it can tell you about your own nature, about this strange world you’ve got to live in, learn in, suffer in, and finally die in. Yes, even you will have to die one day—maybe fifty years from now, maybe tomorrow. Who knows? But it’s going to happen, and one’s a fool if one doesn’t prepare for it.” He turned to Will. “Would you like to come along while we take our shower and get into some clothes?”

“You’re like that mynah,” said Dr. Robert at last. “Trained to repeat words you don’t understand or know the reason for, ‘It isn’t real. It isn’t real.’ But if you’d experienced what Lakshmi and I went through yesterday you’d know better. You’d know it was much more real than what you call reality. More real than what you’re thinking and feeling at this moment. More real than the world before your eyes. But not real is what you’ve been taught to say. Not real, not real.'” Dr. Robert laid a hand affectionately on the boy’s shoulder. “You’ve been told that we’re just a set of self-indulgent dope takers, wallowing in illusions and false samadhis. Listen, Murugan—forget all the bad language that’s been pumped into you. Forget it at least to the point of making a single experiment. Take four hundred milligrams of moksha-medicine and find out for yourself what it does, what it can tell you about your own nature, about this strange world you’ve got to live in, learn in, suffer in, and finally die in. Yes, even you will have to die one day—maybe fifty years from now, maybe tomorrow. Who knows? But it’s going to happen, and one’s a fool if one doesn’t prepare for it.” He turned to Will. “Would you like to come along while we take our shower and get into some clothes?”

Without waiting for an answer, he walked out through the door that led into that central corridor of the long building. Will picked up his bamboo staff and, accompanied by Vijaya, followed him out of the room.

“Do you suppose that made any impression on Murugan?” he asked Vijaya when the door had closed behind them.

Vijaya shrugged his shoulders. “I doubt it.”

I love this exchange because it contrasts the “psychedelic perspective” against the cynical view that dismisses all drug-mediated experiences as delirious nonsense. Why, indeed, must an experience have external reference points to be valuable? In one of my best posts, I elaborate on how tripping can be deeply therapeutic.

Meditation is the Daily Meal; Psilocybin is the Banquet.

In the next excerpt, the main character, Will, asks about the connection between everyday meditation and the infrequent psychedelic mushroom sessions. He wonders why the locals bother with daily meditations when they can take a chemical shortcut to transcendence (page 226):

You can’t have banquets every day. For your everyday diet you have to do your own cooking. The moksha-medicine comes as an occasional treat

“Of course there is,” she answered. “The moksha-medicine takes you to the same place as you get to in meditation.”

“So why bother to meditate?”

“You might as well ask, Why bother to eat your dinner?”

“But, according to you, the moksha-medicine is dinner.”

“It’s a banquet,” she said emphatically. “And that’s precisely why there has to be meditation. You can’t have banquets every day. They’re too rich and they last too long. Besides, banquets are provided by a caterer; you don’t have any part in the preparation of them. For your everyday diet you have to do your own cooking. The moksha-medicine comes as an occasional treat.”

“In theological terms,” said Vijaya, “the moksha-medicine prepares one for the reception of gratuitous graces—premystical visions or the full-blown mystical experiences. Meditation is one of the ways in which one co-operates with those gratuitous graces.”

“How?”

“By cultivating the state of mind that makes it possible for the dazzling ecstatic insights to become permanent and habitual illuminations. By getting to know oneself to the point where one won’t be compelled by one’s unconscious to do all the ugly, absurd, self-stultifying things that one so often finds oneself doing.”

How to Educate Children

The local school principal, Mrs. Narayan, explains the island’s educational approach to Will. One of the exercises is to present the students with a gardenia, and ask them to look at it without any preconceptions or labels. (Page 268)

One can always substitute a bad ready-made notion for the best insights of receptivity. The question is, why should one want to make that kind of choice?

“All this,” Will commented, “sounds very like what Dr. Robert was saying at the initiation ceremony.”

“Of course it does,” said Mrs. Narayan. “Learning to take the Mahakasyapa’s-eye view of things is the best preparation for the moksha-medicine experience. Every child who comes to initiation comes to it after a long education in the art of being receptive. First the gardenia as a botanical specimen. Then the same gardenia in its uniqueness, the gardenia as the artist sees it, the even more miraculous gardenia seen by the Buddha and Mahakasyapa. And it goes without saying,” she added, “that we don’t confine ourselves to flowers. Every course the children take is punctuated by periodical bridge-building sessions. Everything from dissected frogs to the spiral nebulae, it all gets looked at receptively as well as conceptually, as a fact of aesthetic or spiritual experience as well as in terms of science or history or economics. Training in receptivity is the complement and antidote to training in analysis and symbol manipulation. Both kinds oftraining are absolutely indispensable. If you neglect either of them you’ll never grow into a fully human being.”

There was a silence. “How should one look at other people?” Will asked at last. “Should one take the Freud’s-eye view or the Cezanne’s-eye view? The Proust’s-eye view or the Buddha’s-eye view?”

Mrs. Narayan laughed. “Which view are you taking of me?” she asked.

“Primarily, I suppose, the sociologist’s-eye view,” he answered. “I’m looking at you as the representative of an unfamiliar culture. But I’m also being aware of you receptively. Thinking, if you don’t mind my saying so, that you seem to have aged remarkably well. Well aesthetically, well intellectually and psychologically, and well spiritually, whatever that word means— and if I make myself receptive it means something important. Whereas, if I choose to project instead of taking in, I can conceptualize it into pure nonsense.” He uttered a mildly hyenalike laugh.

[On culture:] The thing in whose absence we cannot possibly grow into a complete human being is, all too often, the thing that prevents us from growing.

“If one chooses to,” said Mrs. Narayan, “one can always substitute a bad ready-made notion for the best insights of receptivity. The question is, why should one want to make that kind of choice? Why shouldn’t one choose to listen to both parties and harmonize their views? The analyzing tradition-bound concept maker and the alertly passive insight receiver—neither is infallible; but both together can do a reasonably good job.”

“Just how effective is your training in the art of being receptive?” Will now enquired.

“There are degrees of receptivity,” she answered. “Very little of it in a science lesson, for example. Science starts with observation; but the observation is always selective. You have to look at the world through a lattice of projected concepts. Then you take the moksha-medicine, and suddenly there are hardly any concepts. You don’t select and immediately classify what you experience; you just take it in. It’s like that poem of Wordsworth’s, ‘Bring with you a heart that watches and receives.’ In these bridge-building sessions I’ve been describing there’s still quite a lot of busy selecting and projecting, but not nearly so much as in the preceding science lessons. The children don’t suddenly turn into little Tathagatas; they don’t achieve the pure receptivity that comes with the moksha-medicine. Far from it. All one can say is that they learn to go easy on names and notions. For a little while they’re taking in a lot more than they give out. […] One starts with botany — or any other subject in the school curriculum — and one finds oneself, at the end of a bridge-building session, thinking about the nature of language, about different kinds of experience, about metaphysics and the conduct of life, about analytical knowledge and the wisdom of the Other Shore.”

The Blessing and Curse of Culture

Huxley says it all in one paragraph. I am reminded of Terence McKenna’s assertion that “Culture is not your friend.”

The dancer’s grace and, forty years on, her arthritis—both are functions of the skeleton. It is thanks to an inflexible framework of bones that the girl is able to do her pirouettes, thanks to the same bones, grown a little rusty, that the grandmother is condemned to a wheelchair. Analogously, the firm support of a culture is the prime-condition of all individual originality and creativeness; it is also their principal enemy. The thing in whose absence we cannot possibly grow into a complete human being is, all too often, the thing that prevents us from growing.

Dualism: The Fiction of “I Am”

And one final quote:

Dualism. . . Without it there can hardly be good literature. With it, there most certainly can be no good life.

“I” affirms a separate and abiding me-substance; “am” denies the fact that all existence is relationship and change. “I am.” Two tiny words, but what an enormity of untruth! The religiously-minded dualist calls homemade spirits from the vasty deep; the nondualist calls the vasty deep into his spirit or, to be more accurate, he finds that the vasty deep is already there.

Like what you’ve read so far? Grab a copy of Island on Amazon!

Have you read the book? What did you think of it? Leave a comment!

Liked this post? Subscribe to my RSS feed to get much more!