Psychedelics and Witchcraft — The Truth About Hallucinogenic “Hexing Herbs” The Sordid History of Deadly Nightshade, Mandrake, and Henbane

by Psychedelic Frontier on Oct 28, 2018 No CommentsWere “hexing herbs” really used by witches in medieval times? Are they for healing, cursing, or consorting with the Devil? Learn all about the sordid history of Deadly Nightshade, Mandrake, and Henbane in today’s post.

This text appeared in the original manuscript of Magic Medicine, my new book about the most fascinating psychedelics on the planet, but was cut for length. So this a sneak peek into the finished book, which covers 23 different plants, fungi, fish, and synthetic substances, from ayahuasca and 2C-B to “mad honey” and hallucinogenic sea sponges.

![]()

Woodcut of witches from The History of Witches and Wizards, 1720

Origins and Background

Throughout human history, few plants have commanded as much respect – and fear – as the nightshades. Of the Solanaceae, a family of more than 2,700 distinct species including potatoes, tomatoes, chili peppers, and tobacco, a few particular plants stand out in botanical lore for their disturbing and powerful effects. Mandrake, henbane, and deadly nightshade – along with Datura and Brugmansia – have been known since antiquity as potent medicines, fatal poisons, and key ingredients in witches’ magical potions. A host of legends and superstitions have sprung up around these plants, largely because of their bizarre psychoactive effects and longstanding associations with witches.

The best-known witches’ potion is the infamous “flying ointment.” Applied to the skin, the ointment supposedly enabled witches to fly through the night to attend the Black Sabbath and consort with the Devil himself.

Their appearance, though darkly alluring, does little to mitigate their reputation as devil’s plants. The seedpods of black henbane resemble a jaw full of jagged teeth protruding from a thick and hairy stalk. Each flower sports a dark, pupil-like center surrounded by pale yellow petals crisscrossed by networks of purple veins. The overall impression is of a jaundiced, bloodshot eye.

Deadly nightshade, or belladonna, offers seductively dark, shiny berries alongside its star-shaped purple flowers. Its epithet of “deadly” is well deserved – every part of the plant is poisonous, and as few as five of its deceptively sweet berries can kill an adult.

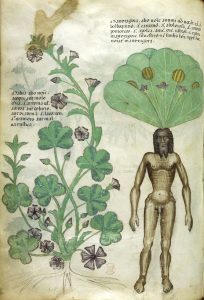

Mandrake’s appearance is perhaps strangest of all. The roots twist in a somewhat humanoid fashion, resembling misshapen dolls with spindly limbs. An old legend, often perpetuated in herbal texts through the centuries, insists that mandrakes scream when pulled up from the earth, and that their cries are fatal to all within earshot. Harry Potter fans will recall the ugly critters from the wizard’s Herbology class, where students had to wear soundproof earmuffs to avoid injury.

A Waking Nightmare: The Experience

Mandrake, henbane, and belladonna all contain tropane alkaloids – a group of chemicals including atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine which cause a variety of strange effects on humans and animals. The tropanes boast a wide variety of legitimate medical uses, ranging from pupil dilation to treating motion sickness, but at higher doses their mental and physical effects are almost universally described as unpleasant.

Because of the high toxicity of these compounds – especially atropine, which is most plentiful in belladonna – accidental overdose is all too easy and extremely dangerous. The risk of poisoning has been recognized for centuries; in a botany text published in 1597, herbalist John Gerarde said of nightshade: “It causeth sleep, troubleth the mind, bringeth madness, if a few of the berries be inwardly taken.”

Though undoubtedly hallucinogenic, the nightshades vary so widely from classical psychedelics like peyote and psilocybin mushrooms that they’ve earned the more sinister moniker of deliriants. Deliriants produce visions in high doses but they also cause – you guessed it – delirium.

The main problem with delirium is the inability to tell hallucinations from reality. Because of the user’s bewildered state, even the most preposterous visions are accepted as real. It’s often described as a waking nightmare, where fact and fiction intermingle in surreal and utterly convincing ways.

Combine that with extreme dry mouth, dizziness, sexual arousal, and agitation, and you have a recipe for a terrible evening. With a typical nightmare, you can wake up and realize it wasn’t real. The nightshades offer more of a Nightmare on Elm Street: you’re already awake, and falling asleep offers no escape. The demonic and threating visions pursue the dreamer until the drug wears off hours later. By morning, you’ve forgotten what transpired.

Witch feeding her familiars with blood, 1579

Understandably, the nightshades are among the least popular recreational substances. Among those brave enough to give them a try, few choose to repeat the ordeal, and many emphatically warn against it. Just witnessing someone’s delirious episode is enough to put many people off these plants permanently.

Descriptions of the experience tend to fall into two categories. Those who take enough to enter a genuine delirium – but, crucially, not enough to paralyze or kill themselves – frequently describe the experience as hellish, terrifying, and demonic.

Other users, erring on the side of caution, take a small dose and experience minor effects. They describe the high as “woozy,” “relaxed,” a bit like drunkenness, but “more lucid.” Visual effects are limited to slight blurriness. Overall it’s not unpleasant, they report, but nothing special either. At such low doses, the user tends to conclude that the nightshades are over-hyped.

On very rare occasions, an experience will fall between these two extremes – neither overwhelming nor dull, with sensations of flight and bizarre hyper-realistic waking dreams. The dose is very difficult to get right – different parts of the plants contain widely different concentrations of active ingredients, and even a single specimen’s chemistry varies with the season and time of day. Herbalists, physicians, and witches in centuries past understood how to use these plants with great precision, but modern users are often flying blind.

History

The nightshades’ effects are generally regarded as unpleasant, but that hasn’t stopped people from using them for a wide variety of purposes since time immemorial. Whether as anesthetics, painkillers, aphrodisiacs, poisons, cosmetics, witches’ potions, or obscure recreational drugs, the nightshades have bloomed in all corners of human history.

When the New World was discovered, Europeans were initially skeptical of plants like tomatoes and potatoes because of their resemblance to the toxic nightshades of their homeland. They were right to be suspicious – though its roots are safe, the fruits of the potato plant contain solanine, a toxic poison. Green potatoes are to be avoided for the same reason.

Seasickness, Surgeries, and Space

Scopolamine – one of the three main alkaloids in nightshades, and the one most responsible for hallucinations and other effects on the central nervous system – enjoys a variety of medical applications today. Once smeared on the skin to produce the sensation of flying, nowadays scopolamine is more likely to help you cross the ocean by ship. A potent anti-nausea medication, it is commonly available as a transdermal patch or topical cream for treating sea sickness. It can even be used for space travel; NASA has developed an intranasal formulation to relieve space motion sickness.

Scopolamine also calms spasms in the digestive tract, treats irritable bowel syndrome, and aids doctors in performing gastric procedures like endoscopies. And like atropine, scopolamine reduces bodily secretions, so it is used to treat drooling – a side effect of some other medications – and to reduce respiratory secretions before operations.

In the slow evolution from magic and herbalism to modern scientific medicine, many ineffective “cures” have been left by the wayside. But scopolamine plants have proved their value, and are likely to remain staples of the healer’s arsenal for a long time to come.

Belladonna

As one of the most toxic plants in the eastern hemisphere, it’s no surprise that belladonna has long figured as a popular poison. The ancient Celts smeared it on their arrow tips, and the wives of two Roman emperors used it to murder their husbands.

Macbeth of Scotland – the historical figure who inspired Shakespeare’s famous play – once used the plant as a poisonous ploy against invaders. Norwegian forces had surrounded the Scottish city of Perth. Advisors to Duncan, King of the Scots, wasn’t worried. Knowing his lieutenant Macbeth would soon arrive with reinforcements, he favored engaging the invaders in battle.

His advisors had a better plan: surrender to the King of Norway and offer to provide provisions to the conquering army. As a sixteenth century historian tells it, “A great quantity of bread was therefore sent, together with wine and ale, into which had been infused the juice of a poisonous herb, that grows abundantly in Scotland, commonly called sleepy nightshade.”

The Norwegians, celebrating their easy victory, fell into a stupor after drinking the ale. When Macbeth made his surprise attack, he found their camp in complete disarray. A few of the invaders awoke and attempted to resist, but for most, death came as “but a continuation of sleep.”

Illustration of Deadly Nightshade, Atropa belladonna, from an 1887 text

A number of murderers and assassins have made use of belladonna over the centuries. One famous case was that of Marie Jeanneret, a Swiss nurse who in 1868 was found guilty of killing at least six people in her care and sentenced to twenty years in prison. Jeanneret’s weapons of choice were atropine – the chief toxic ingredient in belladonna – along with morphine and antimony, a mineral. What made her one of the more remarkable murderers of the age was the seemingly motiveless nature of her crimes, having no grievances against the victims nor anything to gain from their deaths.

But like all serial killers, Jeanneret did have a motive. “She had a morbid pleasure in suffering and death,” explained a contemporary news article. “She positively reveled in the idea that by means of the tiny bottle or the pinch of powder she carried in her pocket she could control the destinies of families and alter all the conditions of human life…She liked it just as some people like slaughtering pheasants or shooting tigers.”

Belladonna’s full Latin name, Atropa belladonna, indicates its twofold nature as both helper and harmer of humans. The genus, Atropa, refers to Atropos, the Fate of Greek mythology who severs the thread of life, deciding when and how death would come to every person.

Deadly nightshade’s name is well deserved – every part of the plant is poisonous, and as few as five of its deceptively sweet berries can kill an adult.

Belladonna, on the other hand, comes from the Italian for “beautiful woman,” probably because of its former popularity as a beauty aid. A potent pupil dilator, belladonna found favor among Renaissance women who – desiring large, dark pupils, the fashion of the day – would squeeze the berry juice into their eyes before batting their lashes at suitors. It was no mere passing fad; Cleopatra once used belladonna berries to the same effect, and the practice enjoyed a resurgence in Paris in the early twentieth century. Even today, ophthalmologists use atropine to dilate patients’ pupils.

Atropine has a variety of other medical uses. The World Health Organization considers it an “Essential Drug” for hospitals around the world, and belladonna plants are still cultivated for pharmaceutical use. Doctors use atropine to decrease lung and saliva secretions before surgery, to speed up a slow heartbeat in emergencies, and to treat lazy eye.

In spite of being a poison in its own right, atropine is also one of the only effective treatments for nerve agent poisonings. First discovered by the Germans during World War II, nerve agents like sarin and tabun have been used in a number of deadly attacks, including genocidal chemical bombings conducted by Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq War, the Tokyo subway attack in 1995, and government assaults on Syrian civilians in 2013. A ready supply of atropine is critical in treating victims of such attacks. Once famous as an assassin’s tool and a medieval chemical weapon, atropine is now better known as a life-saving medicine in war-torn regions and emergency rooms.

Henbane

Where belladonna is rich in atropine, henbane boasts a higher concentration of its more potent – and more hallucinogenic – cousin, scopolamine. The Ancient Greeks knew of henbane’s toxic and psychotic effects, but also held it in high regard as an agent of prophecy. Some scholars have speculated that the famed Oracles at Delphi inhaled henbane smoke before delivering their pronouncements.

Although they consider it a vice, Bedouins in Egypt and Israel have a long history of smoking henbane seeds, alone or with tobacco, right up to the present day.

Based on its effects, a deliriant like henbane may be the last thing you’d throw into a casual mug of beer. But before hops became the standard ingredient for adding bitter flavor to beer, henbane seeds were among many common herbal additives. In fact, Pilsen – one of the great beer capitals of Europe – was originally named after bilsenkraut, the German word for henbane. Long before today’s pilsener, the pale yellow lager that comprises two-thirds of all beer produced in the world, there was the original pilsenkraut: sedating, inebriating, and a little bit delirious.

You won’t find the original Pilsener in any of the city’s beer houses today, though. With the Beer Purity Act of 1516, all ingredients besides water, barley, and hops were prohibited in beer production. But the art of henbane-laced beer did not die out entirely – a few individuals still brew batches of pilsenkraut according to old family recipes. They describe the altered state as “very relaxing,” “otherworldly,” and “surreal,” – a buzz that’s distinctly different than straight alcohol, but much calmer than typical reports of nightshade delirium.

Mandrake

One of the most important magical and medicinal herbs of the Middle Ages, mandrake is largely neglected today. It was known to ancient Babylon, and the Egyptians held it in such high esteem they listed it on the Ebers Papyrus, one of the most important medical documents of the age. Uncovered cuneiform tablets reveal that the Mesopotamians produced a mandrake-infused wine that they called “cow’s eye,” probably because of its pupil-dilating effect. Like henbane, its chief constituent is scopolamine – the more potent, more psychoactive cousin of belladonna’s atropine.

Shakespeare frequently referred to mandrakes. Cleopatra, pining after her absent lover, cries, “Give me to drink mandragora, / That I might sleep out this great gap of time / My Antony is away.”

In Romeo and Juliet, the heroine retreads an old legend about the plants; in a moment of despair, she imagines entombed spirits shrieking “like mandrakes torn out of the earth, That living mortals, hearing them, run mad.”

Mandrake is an effective anesthetic, and has been used this way for thousands of years. Its painkilling qualities are augmented by the confused oblivion it brings to the patient. The Greek doctor, Dioscorides, was the first to describe this practice in 60 CE, and recommended its use for surgery.

Combining nightshades with opium proved especially effective, and painkilling solutions composed of mandrake, opium, and other herbs became common throughout the Roman and Islamic Empires. From the eleventh to sixteenth centuries, the “soporific sponge” reigned as the preferred way to anesthetize patients before surgery. A sponge would be soaked with a solution of mandrake, opium, and hemlock, and then dried. Before surgery, the patient would breathe the fumes from the newly moistened sponge and sink into an oblivious stupor.

Mandrake and other medieval anesthetics fell out of favor with the advent of safer, more effective alternatives like ether and chloroform in the nineteenth century. Yet a modern version called “Twilight Sleep” – an injection of morphine and scopolamine, administered to women during childbirth – briefly emerged in the early 1900s. It was quickly abandoned over concerns for the health of the newborns, and due to mothers’ complaints of having no memory of delivering their own children.

Witchcraft

The nightshades were closely linked to witchcraft in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. Supposedly, these diabolical herbs were used for conjuring demons, hexing innocents, flying to distant locales, shape-shifting, and other nefarious purposes. Such claims should be taken with a grain of salt – not just because they are patently outrageous, but also because they often came from confessions extracted under torture.

Alleged witches admitted to all manner of bizarre crimes under duress – Satanic orgies, crop blights, poisonings, possessions, and anything else they could invent to satisfy the interrogators of the Inquisition. These “confessions” tell us more about the anti-pagan prejudices of the era’s fanatical Christian authorities than about the individuals they persecuted. Most witches were probably innocent of any wrongdoing.

One sleepy American town is indelibly linked to the phenomenon of witch-hunting. In 1692, the colonists of Salem, Massachusetts found 25 of their townspeople guilty of witchcraft and put them to death. Far from an isolated incident, the Salem witch trials belonged to a much larger and long-lived pattern of persecution against supposed witches in the Western world.

The best-known witches’ potion is the infamous “flying ointment.” Applied to the skin, the ointment supposedly enabled witches to fly through the night to attend the Black Sabbath – a demonic orgy, not a heavy metal concert – and consort with the Devil himself. Historical recipes for flying ointment list mandrake, belladonna, and henbane among the ingredients, as well as hemlock and wolfsbane. Animal lard served as the usual base – for this, witches were said to prize the fat of unbaptized children highest of all.

That explains the “witches’ brew,” but about the popular image of witches flying on broomsticks? The origin for that myth is surprisingly salacious. Witches were believed to smear a wooden staff with flying ointment and mount it, so the active ingredients would be absorbed vaginally. According to Jordanes de Bergamo, writing in the fifteenth century:

But the vulgar believe, and the witches confess, that on certain days or nights they anoint a staff and ride on it to the appointed place or anoint themselves under the arms and in other hairy places.

The earliest reference dates to 1324, when an investigation of an alleged witch made a similar claim.

In rifleing the closet of the ladie, they found a pipe of oyntment, wherewith she greased a staffe, upon which she ambled and galloped through thick and thin.

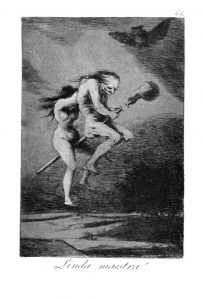

A depiction of witches by Francisco Goya, 1798

Although these allegations may have no basis in truth, they quickly became the stuff of legend. Modern renditions of witches, from The Wizard of Oz to Harry Potter, would appear incomplete without their trusty brooms. If the stories are true, then witches managed to combine drug use, occult magic, and deviant sexuality into one ecstatic act. It’s no wonder the prudish Puritan authorities of the day cracked down on them.

Perhaps the accounts of flying refer not to literal flight, but to the subjective experience of “astral projection.” Many nightshade takers have indicated a sensation of flight and rapid travel, combined with the inability to distinguish dream from reality. It would come as no surprise if “witches” or pagan herbalists, having self-administered tropane alkaloids through the skin, really believed they were soaring through the night sky as their bodies lay in bed.

In retrospect, the Christian authorities of those regrettable years were more deluded than the so-called witches they persecuted. Perceiving threats from all angles – mysterious illnesses, reports of sexual impropriety, pagans who insisted on worshiping the wrong gods, and even the idea of powerful, confident women – they attempted to fight back. But imaginary foes cannot be defeated. People turned on their own neighbors, creating convenient scapegoats for everything they did not understand. For those accused of witchcraft, fear and superstition proved far deadlier than any nightshade.

![]()

Enjoyed this post? This is just one chapter that originally appeared in my book Magic Medicine, about the most fascinating psychedelics in the world. There are 23 more chapters, including LSD, “magic” mushrooms, ayahuasca, Himalayan “mad honey”, and loads more. Check it out here!

Enjoyed this post? This is just one chapter that originally appeared in my book Magic Medicine, about the most fascinating psychedelics in the world. There are 23 more chapters, including LSD, “magic” mushrooms, ayahuasca, Himalayan “mad honey”, and loads more. Check it out here!

Liked this post? Subscribe to my RSS feed to get much more!